Kris Kringle. Ol’ Saint Nick. Santa Claus. Father Christmas. The big guy in red goes by many names. And like all Americans, he is a product of many cultures. From Turkey to the Netherlands, to the Celts, to the Catholics, to capitalism.

Like a Pokémon, Santa Claus has gone through many evolutions to make it to his current form in American myth. He started out nearly two millennia ago in Turkey as Nikolaos the Wonderworker. Then centuries later, the divergent paths of the Celtic Father Christmas and the old Germanic Sinterklaas merged in America into a gumbo called Santa Claus.

But how did St Nicholas become Santa Claus? Well, this story contains so many twists and turns, we’ll have to start at the beginning to get it right.

Nikolaos the Wonderworker and Bishop Nikolaos of Myra

The very first Santa Claus was a probably real man named Bishop Nikolaos of Myra, alive somewhere around the end of the 200s and the beginning of the 300s AD. As a bishop, Nikolaos represented the Ancient Greek city of Myra located in the present day city of Demre, Turkey. His name, Nikolaos, translates from Greek as ‘victory’ (nike-) ‘of the people’ (-laos).1

There’s even evidence Bishop Nikolaos was present at the famed First Council of Nicaea called for by Constantine in 325 AD. The Council of Nicaea is probably most famous for being the first step towards formalizing the Christian religion, establishing it’s rules and doctrine, and leading towards the publishing of the first collected Bible in 400 AD.

Nikolaos the Rhetorician

Fun fact: Nikolaos of Myra was also a student of rhetoric and wrote his own progymnasmata. Progymnasmata were rhetorical textbooks of ancient Greece that “broke down the art of persuasion into manageable units, each of which related to the study of rhetoric as a whole.” 2 Nikolaos’s textbook is noted as being particularly well written, since it “gives clear definitions of each exercise, divides each exercise into parts, and provides suitable models and examples of each.”

Bishop Nikolaos eventually achieved sainthood in the Christian Church, becoming Saint Nikolaos—or to children, Nikolaos the Wonderworker. His feast day occurring on the supposed date of his death, December 6th.

Sinterklaas and Odin the Wanderer

Over the centuries, St Nicholas grew in popularity throughout the Christian world. And over the centuries, the Christian world grew. Tribes of Europe conquered other tribes of Europe. And as each tribe was inducted into Christianity, they brought a bit of their own culture with them.

Saint Nicholas is, of course, an English pronunciation of the Greek man’s name. But in the Netherlands, the Dutch people pronounce his name as Sint Nikolass. He eventually took on the mononym Sinterklass, a portmanteau of Sint Nikolass. In the Netherlands, Sinterklaas carries a staff, rides a huge white horse and has mischievous helpers who spy on children. Each of these features adopted from the Norse god Odin.

Odin’s Influence on St Nicholas

Odin, by the way, was known in England as Woden. And the fourth day of the week is named after him—that is to say Woden’s Day or Wednesday.

In modern society, we tend to Greekify the Ancient myths and religions of other cultures. We call Thor the god of Thunder. Loki is the god of Trickery. And Odin is the kingly god of War, because that is how we were taught polytheistic deities work. But the Ancient Norse religion doesn’t make such clear partitions as that. Much like real people, the Norse gods are complex with a full range of emotions, desires, and personalities. Odin was a ‘god of war’, true. But he was also a god of trickery and witchcraft and wisdom. And yes he was ‘a king’, but he had his high points and low points, like any of us.3

‘Odin the Wanderer’ was one such personality. He had a long beard. Carried a staff. Rode a grand white horse called Sleipnir. And he had mischievous little goblin helpers (which contributed to the word pumpernickel). If you’re trying to picture him, think of Gandalf from Lord of the Rings. Imagine the old man wandering the wilderness, getting up to all kinds of kooky high jinks. As a matter of fact, JRR Tolkien admits in a letter complaining about the illustrated edition of his books, that he based the look of Gandalf very much on Odin the Wanderer:

[Horus Engels] has sent me some illustrations (of the Trolls and Gollum) which despite certain merits, such as one would expect of a German, are I fear too ‘Disnified’ for my taste: Bilbo with a dribbling nose, and Gandalf as a figure of vulgar fun rather than the Odinic wanderer that I think of….4

Old Nick

Nickar or Hnickar is one of the many names of Odin in the old myths5 which has helped contribute to the confusion between ‘Old Nick’ and ‘Old St Nick’.

Father Christmas and the Green Man

Over in Britain, a different winter tradition unconnected with Saint Nicholas took place. Evolving out of the prevailing Celtic traditions of the region, Father Christmas did not don a bishop’s robes of piety or the traveler’s cloak of wily god. Instead, old Father Christmas was a nobleman dressing himself for yuletide festivities.

First appearing in ballads, gests and mummers’ plays (much like Robin Hood) the good Sir Christmas evolved from folk traditions. There are earlier personifications of Christmas appearing as early as the 1400s (and centuries earlier in Yule traditions). But the true Father Christmas really seems to take shape around the 1600s during the tumultuous times of the English Civil War.

Christmas, you see, having no basis in the Bible, was deemed much to Catholic for the newly Protestant nation. And so there were attempts to outlaw the holiday and its pagan personification. But the people were not about to let the government outlaw such a fun and joyous holiday. Regardless of whatever religious implications there were.

So plays and songs and stories featured the good and old Father Christmas. And old Father Christmas begged the people of England to remember him. To remember Christmas. And to celebrate the season with merriment and good beer and good feasting and good cheer. 6

The Green Man

Father Christmas blended Christian tradition with with the Celtic Green Man, where Midwinter represents not cold death, but a birth of the New Year and the coming Spring. Think Falstaff from Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor. Or the Ghost of Christmas Present from Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. He’s jolly and connected to food, nature and rebirth. In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Sir Gawain, a knight of King Arthur’s court, struggles against a woodland deity during Christmas festivities. This is the man Father Christmas became.

Though Father Christmas shares many similarities with Santa Claus, he does not appear to have any relation to St Nicholas. That is until he and the American Santa Claus begin to merge around the turn of the 19th century.

Santa Claus and Old Knickerbocker’s History of New York

Old Nick, isn’t the only connection between Odin and Santa Claus either. Santa Claus is an American corruption of the Dutch Sinterklaas, their nickname for Saint Nicholas.

Washington Irving is the man credited with bringing the Dutch tradition into the greater American culture. Santa Claus grew in the American mythos after Irving publish his very popular History of New York under the pseudonym of Diedrich Knickerbocker. Knickerbocker was a fictional old Dutch man and New York personality created by Irving.

Today, Washington Irving is probably most popular for stories like “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” and “Rip Van Winkle”, but Irving holds a few etymological claims to fame: He was the first person to attach the name Gotham to New York City in the pages of his comedy magazine, Salmagundi.7 And Old Diedrich is actually the origin of the name Knickerbocker as a nickname for New Yorkers (And yeah, the basketball team too).

In the pages of his popular satirical 1809 novel, A History of New York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, by Diedrich Knickerbocker, Irving wrote the following passage, capturing the imaginations of his readers:

And, lo! the good St. Nicholas came riding over the tops of the trees, in that self-same wagon wherein he brings his yearly presents to children. And he descended hard by where the heroes of Communipaw had made their late repast. And he lit his pipe by the fire, and sat himself down and smoked…8

Early Appearances of ‘Santa Claus’

While Irving continued to use the name ‘Saint Nicholas’ in his myth-making, the earliest known use of Santa Claus in print occurs in Rivington’s New-York Gazzette on December 23, 1773. Here the newspaperman states:

“Last Monday, the anniversary of St. Nicholas, otherwise called Santa Claus, was celebrated at Protestant Hall, at Mr. Waldron’s; where a great number of sons of the ancient saint the Sons of Saint Nicholas celebrated the day with great joy and festivity.” 9

Another early citing of “Santa Claus” appears in the New York Evening Post on December 28, 1815 where an op-ed by “Santa-Claus, Queen and Empress of the Court of Fashions” decries the ungentlemenlike tradition of men kissing random women in the time of New Years. And the Empress commands that if a man attempts to kiss one of her female subjects, she should give the man “a hearty box on the left ear.”

If the name seems like a coincidence then I ask you to look to the retort published the following day. A retort by “Sanctus Nicholas, Arch-Emperor of the Fashions” and husband of “Santa Clause”.

Though Clement Clarke Moore’s “A Visit from Saint Nicholas” (aka ‘”Twas the Night Before Christmas”) adds much to the Santa Claus myth, it never uses the term “Santa Claus”. But his other Christmastime poem, “Old Santeclaus”10 obviously does.

Civil War Santa to the Present

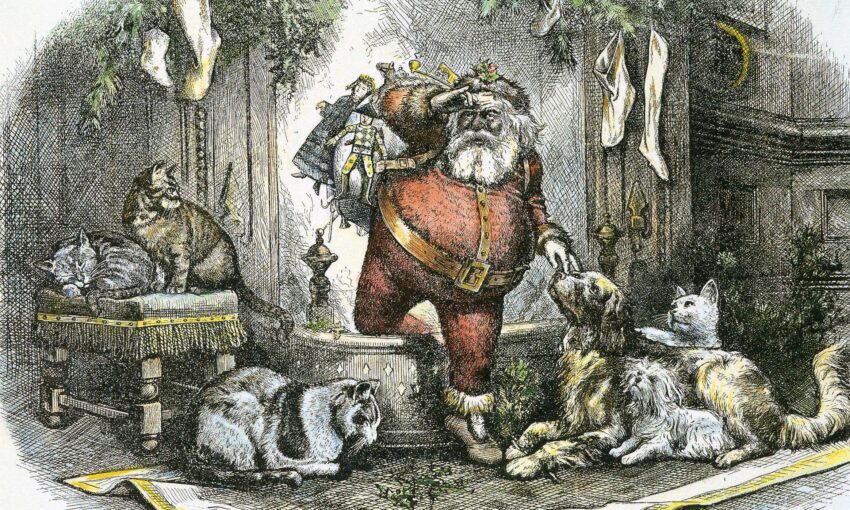

Years after Washington Irving piqued the imaginations of New Yorkers. And years after “A Visit from Saint Nicholas” was anonymously published in 1823, cartoonist Thomas Nast put his everlasting touch on the character.

In the midst of the American Civil War, the political cartoonist Thomas Nast sought to bring Christmas joy to the divided nation in the January 3rd, 1863 edition of Harper’s Weekly. The cover depicts a patriotic Santa sharing presents with Union soldiers and bringing holiday cheer by hanging Confederate traitor, Jefferson Davis, in effigy.11

Nast would go on to illustrate Santa Claus dozens of times for Harper’s Weekly. And over the decades he streamlined the design into something much more recognizable to modern eyes. Santa’s rosy cheeks, white beard, round belly, fur suit and diminutive stature all come from “A Visit From Saint Nicholas”.12 But as with any good cartoonist, Nast was able to make the character instantly recognizable.

Coca-Cola’s Exaggerated Contributions to the Santa Claus Myth

Many people today will claim Coca-Cola invented the modern Santa Claus, but this is a stretch. By the time Thomas Nast finished with him, Santa had his red suit, black boots, fat belt, and was of average human height. Though most might easily recognize the 1931 Haddon Sundblom illustration of Santa Claus,13 he really isn’t that different from Thomas Nast’s later illustrations.

Frankly, Nast’s early illustrations are my favorite representation of Santa Claus: A rotund, little elf-man dressed like an American woodsman. Nast’s Santa is industrious and crafty as any good American should be. He surrounds himself with woodland critters like Father Christmas. He is mischievous and bit pagan like Sinterklaas. And he expresses his piety through child-like miracles like Nicholas the Wonderworker.

- ‘Nicholas‘ | Online Etymology Dictionary

- D’Angelo, Frank J | “The Rhetoric of Ekphrasis” | JAC | 1998

- McCoy, Daniel | “Odin” | Norse Mythology

- Tolkien, JRR | “Letter 106” A Letter to Sir Stanley Unwin | 1946

- ‘Nickar or Hnickar‘ | Brewer’s Dictionary | Bartleby

- Winick, Stephen | “In Comes I, Old Father Christmas”: Surprising History of a Christmas Icon | Library of Congress Blog | 20 Dec 2018

- Langstaff, Esq, Lancelot |”Of the Chronicles of the Renowned and Ancient City of Gotham” | Salmagundi | 11 Nov 1807

- Irving, Washington | Chapter V | Book II | A History of New York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, by Diedrich Knickerbocker |1809

- Moore, Clement Clark | “Old Santeclaus” | Poets.org | 1821

- Lively, Mathew W | “Thomas Nast and Santa Claus in the Civil War” | Civil War Profiles | 22 Dec 2013

- Moore, Clement Clark | “A Visit from Saint Nicholas” | Poetry Foundation | 1823

- “Five Things You Never Knew About Santa Claus and Coca-Cola” | The Coca-Cola Company