Mathematics is a tricky subject for some students. Some brains are wired for math, and some brains are wired for the humanities. Or should I say, some brains are wired for ‘maths’, and some are wired for the humanities? You see, as tricky as math (or ‘maths’) can be, the gift of a linguist is to be able to take any simple, straight-forward subject, and make it needlessly complicated.

You see, in North America when we discuss mathematics, we use the abbreviation math. Though UK English speakers choose to abbreviate the singular mathematic and then pluralize that abbreviation to maths.

British English vs American English

British English speakers will often tease Americans for our misuse of the language that they invented. But according to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the American shortening of mathematics dates back to 1890, while “the British preference, maths, is attested from 1911.” 1

It would seem then that the word was corrupted in the opposite direction over the Atlantic! But other attestations confuse the matter further. For example Lewis Carroll, the writer of Alice in Wonderland and professional mathematician, used the abbreviation math twice in a diary entry from March 29th, 1885:

A book of Math. curiosities, which I think of calling “Pillow Problems, and other Math. Trifles.” This will contain Problems worked out in the dark, Logarithms without Tables, Sines and angles do., a paper I am now writing on “Infinities and Infinitesimals,” condensed Long Multiplication, and perhaps others. 2

Carroll’s diary entry comes 5 years before the Online Etymology Dictionary’s first attestation of ‘math’. And interestingly enough, it occurs in England by an Englishman.

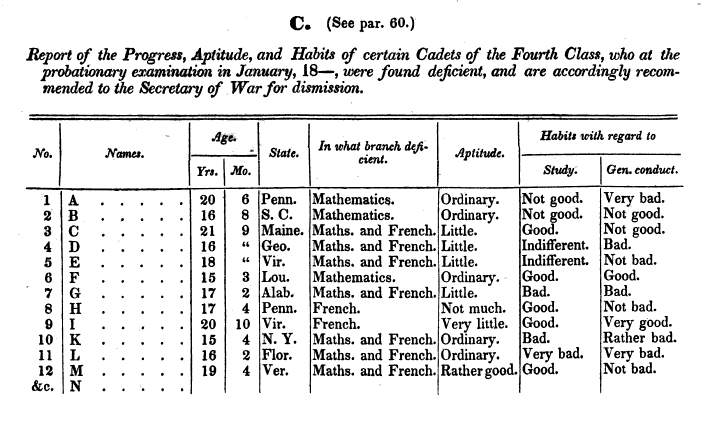

And yet, even earlier than Carroll’s use of math, American examples of maths have appeared in print. Throughout the 1860s, a series of ads in The American Educational Monthly heavily committing to the abbreviation maths 3. And in 1832, a West Point manual entitled, Regulations of the US Military Academy, at West Point also used the abbreviation maths 4.

Though in the examples above, math and maths are used as shorter versions of the word mathematics in publications where space is limited. Notice how each example includes a period after the abbreviation? And in the example from West Point, maths only appears in a table where mathematics will not fit. Elsewhere in the table (and throughout the rest of the manual), the writer favors the term mathematics.

When Does an Abbreviation Become a Word?

Which brings up an important question. Since people often improvise abbreviations on an ‘as needed’ basis, when does an abbreviation gain enough acceptance to become a word in its own right?

Surely in the millennia long history of the word mathematics and its ancestors (mathematique in Old French, mathematica in Latin, mathēmatike tekhnē in Ancient Greek), countless people must have started writing the word mathematics, run out of room on the page, and just stopped at any random point. M, mathe, mthmtcs, math and Maths are all valid abbreviations depending on the context.

But Math and Maths are not just abbreviations. They’ve become words in their own right. It’s perfectly natural for a person to say, ‘I teach math.’ But no one would say, ‘I teach Eng.’ Neither math nor maths are simply abbreviations. They are words.

This puts math and maths in a pretty special category of word. They’re not acronyms which shorten a series of words—like how laser means ‘light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation’. Nor are they a single word shortened phonetically—like donut for doughnut or thru for through. Math and maths began life as a longer word, became shortened and slowly began to replace their predecessor—like how telephone became phone or how advertisement became ad.

To Pluralise or not to Pluralize

Each version of the word does a little something different though. Math is a ‘shortening’ of mathematics, while maths is a ‘contraction’ of mathematics. The contraction benefits the reader by indicating the plural word. But then again, mathematics is singular in its construction (notice how I used the word is). So perhaps math is a better representation.

In The King’s English (published in 1908), HW Fowler had nothing to say about math or maths. Perhaps they didn’t gain popularity until after his passing. But he had quite a bit to say about Americanisms.

Though we take these separately from foreign words…the distinction is purely pro forma; Americanisms are foreign words, and should be so treated. To say this is not to insult the American language. … It must be recognized that they and we, in parting some hundreds of years ago, started on slightly divergent roads in language long before we did so in politics. 5

Regardless of who first used math or maths, regardless of who originated the language, it is clear American English and British English became different languages long ago. And so they will evolve in their own ways. Whether you use math, maths or mathematics, remember that English conforms to its users. And nothing in linguistics is as simple or straight-forward as math(s).

- “Math” | Online Etymology Dictionary

- Collingwood, Stuart Dodgson | Chapter VI | The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll | 1899

- The American Educational Monthly | 1864

- Figures C & D | Regulations of the US Military Academy, at West Point |1832

- Fowler, HW | “Americanisms” | Chapter 1: “Vocabulary” | The King’s English | 1908