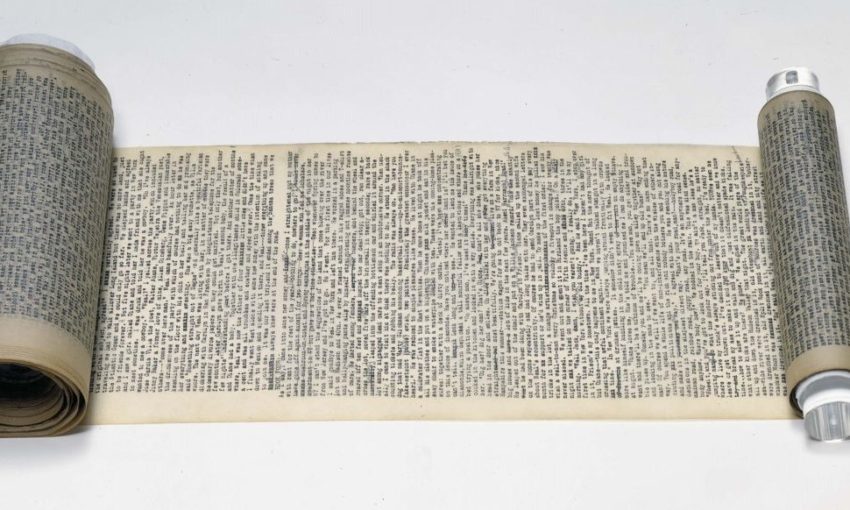

In the early 20th century, innovative writers like EE Cummings pushed the boundaries of poetry with their tools of creation. Just as dramatists and orators of the Classical era used devices like rhyme, alliteration and meter to make their works easier to memorize, Cummings crafted his poems to suit the constraints of his medium—namely, the typewriter. Decades later, Jack Kerouac became famous for his “spontaneous prose”—a writing style he nurtured by using an augmented Underwood fixed with scroll attachment 1. Writers who seek to innovate do so by exploring the options their medium provides.

In the years since Cummings, the tools have changed. Though many written works have migrated to digital platforms, many writers still haven’t learned the intricacies of digital culture. If modern writers want to push the boundaries of typography, design and writing, they need a contemporary understanding of all three fields.

Many writers seeking to innovate are still caught in the typewriter frame of mind. While digital word processors present whole new options for how words appear on a page, they bring new constraints as well. The traditions of ‘concrete poetry’ don’t work in a fluid medium. Trying to apply typewriter tricks on the Web will only lead to frustration when those tricks don’t translate. Writers and editors need to understand and be able to manipulate the code that comprises their written works. Only then can they develop new tricks for the new medium.

Digital Publishing Takes Control Away from Creators and Gives It to Users

The reason digital publishing can be such a complicated process for writers is because it’s designed to give control to the user rather than the content creator. In print, writers—and to a greater extent, publishers—are given the type of control that is easy to take for granted. The publisher sets the font size, style and type. The poet chooses where line breaks occur and other typographic flourishes. The writer can choose to blend illustrations into the story at specific moments in the text (like in Alice in Wonderland and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas).

But with digital media, these options are not always available to creators. Think about how you access your content. How that content appears all depends on what device you’re using—a tablet, smart phone, desktop, laptop—all of which have different screen resolutions, aspect ratios, operating systems, software, software versions and user settings. Many programs also try to give as many options to the user as possible which limits a creator’s control. Millions of subtle little changes may occur between what a writer publishes and what a reader sees.

In Walter Benjamin’s 1936 essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, he argues that “even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space” 2. When works of art are mechanically reproduced, the art appreciator is always seeing a distortion of the original work. And these distortions become more nuanced in the age of digital reproduction.

Writers and Editors Need a Foundational Understanding of How Their Content Is Built

Blog publishing services like WordPress, Blogger and Tumblr make publishing on the Web easier than ever. And the ability to publish PDFs on services like the Amazon Marketplace or Issuu turns anyone with Microsoft Word into a publisher. But these plug-and-play, WYSIWYG consumer products rely on automated functions to provide their services.

In Lev Manovich’s book The Language of New Media he states,

“Numerical coding of media and the modular structure of a media object allow for the automation of many operations involved in media creation, manipulation, and access. Thus human intentionality can be removed from the creative process, at least in part.”

Blog publishing services rely on automated functions to provide their services. And these automated functions remove human intentionality from the creative process. If writers want greater control over their works, they need to learn where automation occurs and how to reduce it.

Fonts Are Relative

Understanding how fonts are used is one of the most effective ways to tell how your text will behave on a digital platform. Writers will often use tabs and spaces to align words, but this only works if the font is consistent. In monospace typefaces each character is the same width (which makes it easier to maintain a consistent spatial relationship between text). But with proportional typefaces the width of a character will vary depending on the character itself and the font used. So for example, if you submit a manuscript in Times New Roman, your work will distort if the website loads in Helvetica.

Identifying the house typeface of a website is a good way to anticipate these changes. But even then, many websites will assign multiple typefaces to remain accessible to all users. Then there’s the fact that many browsers allow users to set their own typefaces (and sizes) which throws another wrench into the process.

Your Word Processor Will Define Your Work

Understanding the functions of different word processors can also help writers understand how a manuscript will transform before it’s published. Microsoft Word has become as ubiquitous among writers as typewriters once were. But Word is oftentimes the worst word processor for a digital writer to use. Word is a fine tool for print purposes, but there are key features that make it inadequate for digital publishing. Notably, Word’s units of measurement do not translate to screen media. Word measures it’s text area in inches (most usually 8.5″ x 11″) which is unsuitable for screens which are measured in pixels. And Word measures fonts in points (which are most suitable for print) rather than ems, pixels and percentages which is how fonts are measured in digital media.

Ideally, writers would create using similar platforms to the ones their work will be published with. This would allow writers interested in the visual aspect to see something similar to readers. Using programs like Mou will allow writers to incorporate HTML or Markdown into their text and see the results of that code side by side.

Web Design Concepts Writers Should Consider:

Most literary magazines will encourage submitters to read back issues before submitting (so that they can get some idea of what the magazine publishes), but writers should also consider other typographic and design elements before submitting. Some include (but are not limited to):

- identifying the house typeface and style guide (which is always more specific than just MLA or Chicago).

- calculating the width of the text area. There are tools to help you do this.

- learning the differences between common document file types (eg DOC, DOCX, RTF, TXT, PAGES and PDF).

- learning the difference between ems, pixels, points and percentages and how they’re used.

- identifying fluid layouts vs fixed layouts and which one your submission will be subject to.

- manipulating HTML tags such as paragraph (<p>), line-break (<br/>) and non-breaking spaces ( ) and CSS properties such as “white-space“.

Needless to say, these techniques become more coherent with a foundational understanding of HTML and CSS. For writers or editors interested in learning, Codecademy is an easy way to learn code online, for free and at your own pace.

Writers Need to Trust Their Editors

As writers continue experimenting with typography and blur the lines of prose, verse and graphic design, it becomes increasingly difficult for editors and publishers to rely on the WYSIWYG text editors that services like WordPress provide. The more writers experiment, the more they present new challenges for editors to solve. So editors of online publications need to understand the behavior of the code behind their content.

Preferably, writers who submit to digital publications would already know how everything works at the beginning of the creation process. But at the present that’s an unrealistic ideal. This is why writers need knowledgeable editors. An editor for an online or digital publication should hopefully be knowledgeable enough about the medium they publish in to give informed advice to writers who wish to create for that medium. The flip side is that writers need to trust the advice of those editors. Because, as I’ve said before, good editors make for better art. If the written work is like a lens, then the editor is like an optometrist calibrating and prescribing it to the proper audience. An editor needs to be able to see the big picture and ensure that a creative work is meeting its goals.

Not All Writing Needs to Be Published Digitally

Publishing on digital platforms demands that writers and editors have a basic understanding of how these platforms function. It also demands that writers conform to the constraints set by the technology, its manufacturers and its users. But this is not to say that all writing needs to adapt to this technology. An artist needs to understand his/her medium, but ultimately the artist still gets to choose the medium.

If the thing a writer writes will work best in print, then why not just publish it in print? Buy a typewriter (yes, for some reason they’re still being manufactured), support your print publishers, create something material/tactile/real. Engage our senses—teach us something we couldn’t have learned off of a computer.

Digital publishing isn’t a replacement for print (just as film wasn’t a replacement for theatre). In fact, it’s an entirely new medium with its own strengths and weaknesses. And it’s these strengths and weaknesses that writers must consider before submitting.

- “Jack Kerouac” | myTypewriter.com

- Benjamin, Walter | “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” | 1936